ST. LOUIS, Missouri, March 8, 2025 (ENS) – A new low-cost sensor that detects airborne H5N1 avian flu in under five minutes sounds mighty good as bird flu continues to spread, infecting 70 people in the United States in the past 11 months, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta has confirmed. One person has died.

The contagious virus has spread to include wild birds, both commercial and backyard flocks of chickens and turkeys, and dairy cows in several states.

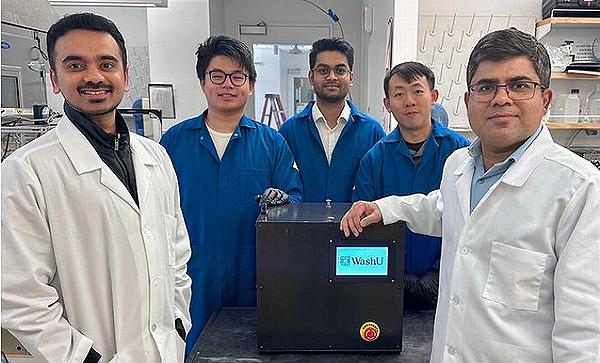

Developed by scientists at Washington University in St. Louis, the sensor could be used in large agricultural operations to monitor bird flu outbreaks.

Formally known as highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza, in recent years, bird flu has been detected in mammals including: foxes, bears, and seals; cats and dogs; goats, cows, and mink; and even tigers and leopards in zoos.

As bird flu continues to spread, both farmers and public health experts need better ways to monitor for infections, in real time, so they can quickly respond to outbreaks.

As published in a special “breath sensing” issue of the American Chemical Society’s journal ACS Sensors, the research resulted in a prototype of the device. It would give virus trackers a way to monitor aerosol particles of H5N1 in real time.

To create their bird flu sensor, researchers in the lab of Dr. Rajan Chakrabarty, a professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering at WashU’s McKelvey School of Engineering, worked with electrochemical capacitive biosensors to improve the speed and sensitivity of virus and bacteria detection.

But converting the biological information to an easily processed electronic signal is challenging due to the complexity of connecting an electronic device directly to a biological environment, explained a group of Swiss sensor scientists at ETH Zurich who did not participate in the Washington University research.

“Electrochemical biosensors provide an attractive means to analyze the content of a biological sample due to the direct conversion of a biological event to an electronic signal,” they wrote back in 2008.

The idea for bird flu biosensors has been floated in the past, but Dr. Chakrabarty’s lab is the first to make a prototype.

“This biosensor is the first of its kind,” said Chakrabarty, speaking of the technology used to detect airborne virus and bacteria particles. Scientists previously had to use slower detection methods with polymerase chain reaction DNA tools.

Chakrabarty says conventional test methods can take more than 10 hours, which he says is “too long to stop an outbreak.”

The new biosensor works within five minutes, and preserves the sample of the microbes for further analysis. It provides a range of the pathogen concentration levels detected. This allows for immediate action, he said.

Time is of the essence when preventing a viral outbreak. When the lab started working on this research, H5N1 was only transmissible through contact with infected birds.

“As this paper evolved, so did the virus; it mutated,” Chakrabarty said.

The United States tracks animal health and the pathogen outbreaks on farms through the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), which last reported that in the past 30 days, there have been at least 35 new dairy cattle cases of H5N1 in four states, most in California.

The spread of bird flu has caused the slaughter of over 100 million laying hens in the United States, skyrocketing egg prices, a growing number of human infections and the first human death, when .

“The strains are very different this time,” Chakrabarty warned.

In the past, when farmers suspected illness, they could send the animal to state agriculture department labs for testing. But this slow process can be further delayed due to the backlog of cases as H5N1 overtakes poultry and dairy farms.

Once bird flu is detected, options include biosecurity measures such as quarantining animals, sanitizing facilities and equipment, and protective controls to limit animal exposure, including mass culling.

More relief for farmers eager to lower egg prices is on the horizon. On February 14, the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Center for Veterinary Biologics issued a conditional license for an avian flu vaccine to the animal health company, Zoetis of New Jersey for use in chickens. The conditional license was granted on the demonstration of safety, purity, and reasonable expectation of efficacy based on serology data.

How the Biosensor Works

Dr. Chakrabarty is ready to introduce his biosensor to the world, saying it was built to be portable and affordable for mass production.

About the size of a desktop printer, the biosensor can be placed where farms vent exhaust from chicken or cattle housing. The integrated pathogen sampling-sensing unit is based on interdisciplinary engineering. Its “wet cyclone bioaerosol sampler” was originally developed for sampling SARS-CoV-2 aerosols.

The virus-laden air enters the sampler at high velocities and is mixed with the fluid that lines the walls of the sampler to create a surface vortex, trapping the virus aerosols. The unit has an automated pumping system that sends the sampled fluid every five minutes to the biosensor for virus detection.

The biosensor uses “capture probes,” single strands of DNA that bind to virus proteins, flagging them. The team’s big challenge was finding a way to get these aptamers to work with the 2-millimeter surface of a bare carbon electrode in detecting the pathogens.

After months of trial and error, the team figured out the right recipe for modifying the carbon surface using a combination of graphene oxide and Prussian blue nanocrystals to increase the biosensor’s sensitivity and stability.

The final step involved tying the modified electrode surface, the “secret sauce” for enabling a bare carbon electrode to detect H5N1.

One big advantage of the team’s detection technique is that it is nondestructive. After testing for the presence of a virus, the sample can be stored for further analysis by conventional techniques.

The integrated pathogen sampling-sensing unit works automatically – a person doesn’t need to have expertise in biochemistry to use it. It is made with affordable and easy-to-mass-produce materials.

The biosensor can provide concentration ranges of H5N1 in the air and alert operators to disease spikes in real time, and let operators know if the pathogen balance has tipped into dangerous levels.

That ability to offer a range of virus concentration is another “first” for sensor technology. Most importantly, it can potentially scale up to find many other dangerous pathogens all in one device.

“This biosensor is specific to H5N1, but it can be adapted to detect other strains of influenza virus such as H1N1 and SARS-CoV-2 as well as bacteria like E. coli and pseudomonas in the aerosol phase,” Chakrabarty said.

Now, the Washington University team is working to commercialize the biosensor with Varro Life Sciences, a St. Louis biotech company that has consulted with the research team during the biosensor’s design stages.

USDA Offers $1 Billion Toward Bird Flu Plan

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins has proposed a $1 billion-dollar strategy to curb highly pathogenic avian influenza, protect the U.S. poultry industry, and lower egg prices. Announced on February 26, this funding is in addition to funds already being provided to indemnify growers for depopulated flocks, Rollins said.

The strategy includes an additional $500 million for biosecurity measures, $400 million in financial relief for affected farmers, and $100 million for vaccine research, action to reduce regulatory burdens, and exploration of temporary import options, she said.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) continues to believe the threat to the general public remains low. State and federal animal health experts believe that it remains safe to eat egg and poultry products cooked to an internal temperature of 165˚F.

Even so, Rollins says the USDA will be “hyper-focused on a targeted and thoughtful strategy for potential new generation vaccines, therapeutics, and other innovative solutions to minimize depopulation of egg laying chickens along with increased bio-surveillance and other innovative solutions targeted at egg laying chickens in and around outbreaks.” Up to a $100 million will be available for innovation in this area.

The Secretary said the USDA will work with trading partners to limit impacts to export trade markets from potential vaccination.

The agency will solicit public input on solutions, and will involve governors, state departments of agriculture, state veterinarians, and poultry and dairy farmers on vaccine and therapeutics strategy, logistics, and surveillance.

Rollins said that the USDA will immediately begin holding biweekly discussions on this and will brief the public on its progress biweekly until further notice.

Featured image: Chickens at a commercial poultry farm. undated (Photo courtesy APHIS, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture)